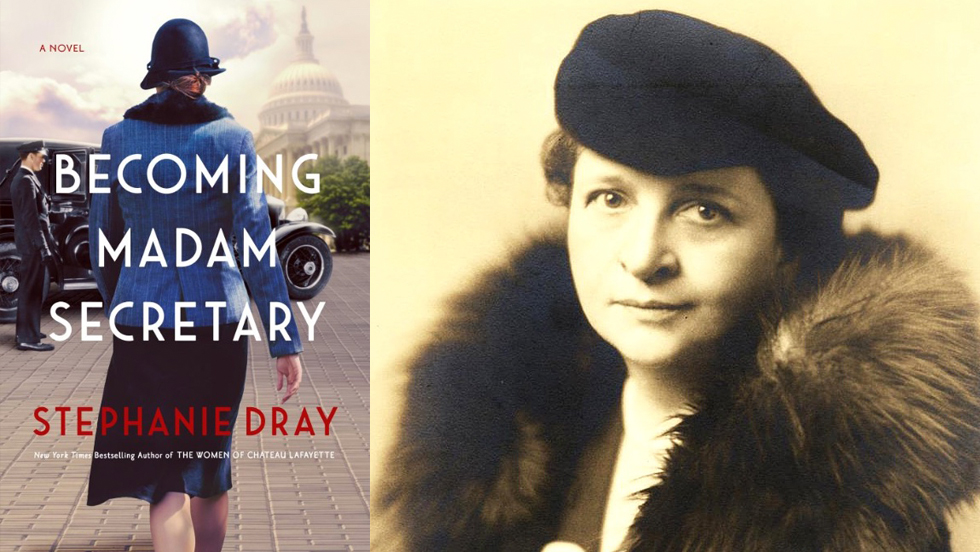

Frances Perkins went from professor of sociology to President Franklin Roosevelt’s secretary of labor—and a lifetime of pioneering social justice reform. Her story inspired novelist Stephanie Dray to make her the subject of her latest book, Becoming Madam Secretary (Park Books, 2024), which is coming out just in time for Women’s History Month.

Robert Linné, PhD, professor of education and cultural studies, School of Education, Ruth S. Ammon College of Education and Health Sciences

Frances Perkins rightfully serves our Adelphi University community as a patron saint. Not only did Perkins teach at Adelphi as a professor of sociology early in her career, she went on to become one of the most impactful public servants in US history as the lead architect of The New Deal.

Although historians understand Perkins as one of the central characters of our American story, her public image has faded to sketchy at best. When I was researching Perkins for my first book on the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, the travesty of her relative obscurity nagged at me as an educator. Once, while holding a letter FDR had sent her, I thought: surely this amazing life would make a great film or novel.

Recently, when I learned that Stephanie Dray, the New York Times–bestselling author of several works of historical fiction, was coming out with a novel about Perkins, I reached out for an interview. The author and I discussed how historical fiction, with Perkins as protagonist, may deepen our understanding of this American hero.

Stephanie Dray, author of Becoming Madam Secretary

How did you become interested in Perkins as a protagonist?

The spark to write about Frances Perkins kind of found me. You see, my family’s stories are a bit like a patchwork quilt of the American dream—newcomers carving out a life, full of grit and grace. My grandparents lived through the Great Depression, and, boy, did they have stories to tell about hunting frogs and picking wild mushrooms just to eat. My great-uncle—then a teenager—died in an attempt to steal coal to keep the family from freezing to death. Now, because of that, and the way the New Deal helped my family survive, FDR was always a household hero for us. But Frances Perkins? She was never mentioned. So learning about her was like uncovering a hidden chapter of history, and when I realized how she was right there in the trenches, fighting the good fight, before Roosevelt ever thought to, I knew her story was the one I needed to tell. This novel is a tribute both to her and to my grandparents—a way to bridge my family’s tales of resilience with Perkins’ incredible journey. I’m so happy to be able to shine a light on this remarkable woman who shaped modern America.

Perkins seems to be frozen in our collective imagination as her older, matronly persona: the original wonk. Did you have fun writing her as youthful?

I had the most fun writing about her dashing and vibrant years as a young person! In fact, I wrote many more scenes of her youth than ever made it into the book. I loved how morally and physically courageous she was, going undercover, tangling with criminals, and living in the heart of dangerous neighborhoods. I loved the way Sinclair Lewis brought out a silly side otherwise not in evidence. I even loved her youthful struggle to find a direction—flirting with acting, writing, teaching and more—when her life’s mission was there in her blood and she’d been right about it from the start.

In most historical images, Perkins’ look is defined by extreme hats, of all things. Is fashion important to your telling of her story?

Gosh. We both know she would’ve hated this question so much, but I love it. I think it’s illustrative of the time she lived in and the challenges she faced as a woman that she felt that she had to cultivate a decidedly unfashionable but iconic look to be taken seriously. She says that tricorn hat became her trademark because her mother told her it was the only shape she could pull off, and I believe her. But she also knew what she was doing in evoking a spirit of revolution with that hat—in reminding people that she wasn’t some wild-eyed newcomer to the American scene, but that her ideas were deeply rooted in the nation’s history. So the fashion is important in showing how society tried to constrain her and how she fought back on every level, with every stitch of clothing she wore.

How much of a role does New York City, or the nascent bohemian culture of the Village, play in your narrative?

In my opinion, Maine may have had a piece of Frances’ soul, but it was New York City that really stole her heart, and I tried my best to capture that, especially her early days in Greenwich Village. Some might wonder how she meshed with the bohemian vibe, given her straitlaced nature, but I think she thrived on the buzz of ideas, from the outlandish to the groundbreaking. It’s amazing how many friends she made for life during that time, showing just how much it meant to her. It’s a beautiful mix of contrasts that really shows off who Frances was.

My archival research, as well as my visit with Perkins’ grandson at their Maine home, revealed many surprises. My most memorable discovery was a box of her lecture notes from her time as a sociology professor at Adelphi. Her voice seemed so far ahead of her times. What “aha moments” highlighted your research?

I think the biggest surprise was the poem she wrote about her husband shortly before he was committed. I had always taken her flippant comments about why she married at face value. She made it sound like she just wanted to get it over with. This certainly fit in with the narrative that she had a pretty terrible marriage. But the heartfelt poem she wrote about how Paul was the only person to ever make her feel as if she wasn’t alone—combined with the loving letters they exchanged—made me reevaluate everything. Certainly they did have a troubled marriage, but they also had a tender and emotionally intimate marriage, and that’s just the sort of complexity one might expect from a woman like Perkins.

How did you approach the relationship between Perkins and FDR? How much do we really know about their personal dynamic?

I think we only know what she was willing to share—but that alone is hilarious. In The Roosevelt I Knew (Penguin Random House, 2011), she goes out of her way to tell us what an unimpressive rat bastard she thought he was when they first met. She seemed tickled by the twist of fate that would make her forever associated with a man she initially couldn’t stand. And that, in turn, tickled me. Obviously, the evolution of their relationship was important to her, which made it important for my novel, and I enjoyed dreaming up specific scenarios that could account for the general changes she describes in their relationship. It’s plain that she loved him as a dear friend and cherished leader to whom she was enormously loyal. But I also think he exasperated her enough that she could remain clear-eyed about his faults.

How did you make decisions about including the horrors of the Triangle Factory Fire in the novel?

I initially did not want to include it, in part because my dear friend and sometimes co-author Laura Kamoie had an idea for us to write a book about just this incident alone. But over time, it became clear that I couldn’t tell the story of Frances Perkins without including this pivotal event, and, thankfully, Laura gave me her blessing. This doesn’t mean we won’t later write that other book about the fire—there’s a lot more to unearth—but I didn’t hold back.

What can a novelized version of Perkins offer your readers that a straight history text might not?

As you know, there are many marvelous biographies of Frances Perkins. Some even do a bang-up job of trying to pull back the curtain on her emotional life. I think this is important because part of the reason Frances Perkins isn’t better remembered is precisely because she did everything possible to obscure her personal story. But people remember stories and, as is often said, novelists can go where historians rightfully fear to tread. By speculating about all the things Frances Perkins would have been infuriated to have me speculate about, I hopefully make readers feel something about this extraordinary American heroine other than simply academic or intellectual admiration.

Many progressive policy goals that Perkins would champion today—affordable, quality childcare for all; improved healthcare outcomes for mothers and children; equal pay; humane integration of immigrants—have been stalled for decades. What would Frances Perkins do?

Like Churchill, she would never, ever give up!

Rob Linné, PhD, is a professor of education and cultural studies at Adelphi. Publications informed by his research on Frances Perkins include: The New York City Triangle Factory Fire (Arcadia, 2011), and The Triangle Factory Memorial (2023).