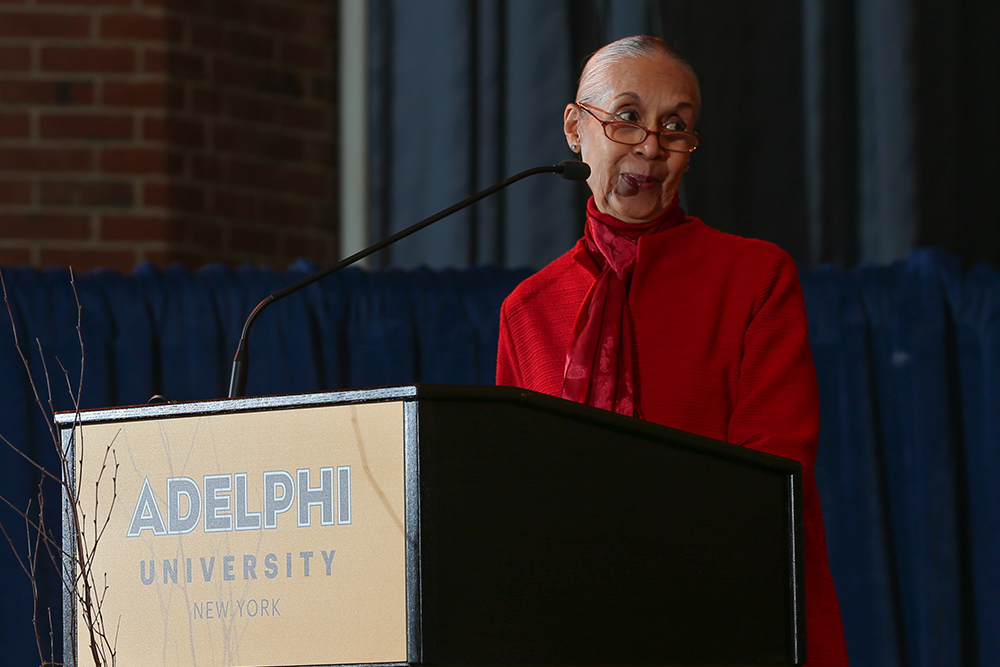

Carmen de Lavallade '03 (Hon.) made headlines when she was named a Kennedy Center honoree for her illustrious career.

“This is my life. It’s like a tapestry.”—Carmen de Lavallade

Carmen de Lavallade ’03 (Hon.) made headlines when she was named a Kennedy Center honoree for her illustrious career. She has danced on stage, television and in film, for such renowned choreographers as Lester Horton, Agnes de Mille and her lifelong friend, Alvin Ailey, and collaborated with a who’s who of some of the greatest artists of the twentieth century, including her late husband, dancer/actor/choreographer Geoffrey Holder (their lives were the subject of the documentary Carmen and Geoffrey). De Lavallade also served as director of Adelphi’s Department of Dance for two years. In October, she came to campus to be honored as an Adelphi Legend, and to sit down with us to reminisce about her career, the many luminaries she’s known, teaching, and experiencing racial discrimination.

Can you tell us about your very varied career?

I suppose it started in Los Angeles, California. I remember my first little dance class, with Melissa Blake. Then I got a scholarship to Lester Horton [Dance Theater]. We didn’t have a classroom so much, the classroom was the stage.

One of the great dancers, Bella Lewitzky, was Lester’s muse. We performed every Friday and Saturday night. I learned a lot about stagecraft because Lester made you work on the stage crew, sweep the floors, make the costumes, build the sets. You were a part of the theater, not just taking class. You really knew your craft when you left the theater. And that served me the rest of my life.

My ballet teacher, Carmelita Maracci, was friends with Lester Horton. In a way, she was very much like Lester. They were people that gave you imagery to work with, not counts. She was [a proponent] of the Cecchetti [Method], which I found very pleasing. I don’t care for the Russian ballet very much. It’s too stiff for me. But I like the delicacy of the Cecchetti. Then I met [dancer, choreographer and director] Jack Cole. You can’t beat Jack Cole for a teacher. I danced in a film called Lydia Bailey [choreographed by Cole].

After Lester passed away, Alvin [Ailey] and I left for New York City to join House of Flowers. Herbert Ross was the choreographer. I met Herbie on the film Carmen Jones. He asked Alvin and I to come join House of Flowers because he was taking over for another director.

Alvin and I get there and it was House of Flowers and Truman Capote and Harold Arlen, and there I met my husband, Geoffrey Holder. Pearl Bailey and Diahann Carroll were in the Carmen Jones film. So it all starts to weave. I’m connected with people in the strangest ways, like a tapestry, and it was really quite wonderful.

New York was where all the big modern dance and ballet companies were. The plays! Tea and Sympathy. The Palladium. Tito Puente…Latin music was really big at that time. The art world was blossoming. It was very exciting.

That’s where I met John Butler. So the next thing you know, I’m working with John Butler, Geoffrey, Alvin, Louis Johnson, Agnes de Mille.

In the Metropolitan Opera, my cousin Janet Collins was the prima ballerina, the first person of color to be prima ballerina at the Metropolitan Opera. And I followed in her footsteps, which is really lovely.

After a while I ended up at Yale University, at the Yale Repertory Theater, teaching movement to the actors. But I also was a part of their company. I performed a piece on television with Mildred Dunnock that was choreographed by John Butler, a poem by François Villon [“The Old Lady’s Lament for Her Youth”] about the old woman losing her youth and thinking about the past.

I met Robert Brustein there and the next thing you know I was teaching the actors movement. That’s when my dancing became better because dance is really like being in the military. It’s so precise and you have to do what the choreographer wants you to do. You very rarely ask questions or say, “No, I don’t think that feels right” or “I don’t want to do that” or “It doesn’t make sense.” When I was asked what I thought about something, I didn’t know. “Just tell me what to do and I’ll do it.” But I had to learn to free myself from that.

When I went back to my dancing it was much richer because I questioned myself. Why am I doing this? I would watch a dance or go to the ballet and I would say, “What are you doing? Why are you doing a brisé there when it doesn’t belong? Because we’re storytellers. The difference between dance now and when I was coming up was that we were storytellers. Now, physically, people are incredible and it’s very acrobatic, but there are no stories anymore.

I found that I grew a lot because of the theater. [In dance, music and live theater] it’s different every day. You don’t play a character the same way. You don’t dance the same way. I watched performers like Al Pacino, who was performing in Salome, and I would love to watch him every night because I never knew what I’d see or hear. Some nights would be better than others, but you can’t say it wasn’t interesting. It was wonderful. And yet around him, there were actors who said the same thing, the same way, with the same intensity, every single night. And that’s when I knew: You have to explore.

I often wondered why [universities] had arts and sciences together. They’re very close, both about problem-solving and being creative. That’s why many people in the sciences play instruments. I was watching a program about the physics of basketball players. I thought, Whoa, what about dancers? It’s physics. In partnering, you have to feel the other person’s weight. You have to be able to jump right into their arms from a distance and know those distances and the weight that hits.

The arts are about solving problems. How do you get from this place to that? How am I going to read this line? What do I feel here? If you’re in a dance, you change theaters. You might have had a huge stage the night before and now you have a stage half that size. How are you going to deal with that? Especially if you have other people around you? How do I get into this costume? What about the lights? Can I be seen? Is the light going to blind the dancers or the actors?

How did you became the director of Adelphi’s Department of Dance?

Nick Petron [Department of Theatre professor and chair] asked me if I would like to take over the dance department. I thought it might be interesting. I had been a performer so it was not the easiest thing to try to organize a department. It was a learning curve for me. I found it very difficult in the beginning because it’s more regimented than I’m used to. I was kind of a free spirit. I find that I’m not a technical person, so to speak, I’m more of a mentor or a tutor. I always had the people that are good at teaching the technique. What was important for me [with teaching] was how to find your energy so that you’re not just on that stage speaking words or dancing steps. You have to include your audience so that they’re your partner. Some people will just dance for themselves and count and that’s the end of that. But you have to include the energy of the audience and your energy together, if that makes any sense.

I always believed that you have to give everyone that chance to find themselves on the stage. Some people were not physically proficient maybe in the technique but there was something about them that was interesting. I see people who physically are just gorgeous and dull. I’m not interested. And there are some people who are not quite as beautifully turned out but there’s something about them in their soul, or something they have about them, about their work, that they believe in.

And that’s what I go for when I teach. I think it’s important [to learn] not only the technique but what’s behind it. Are you telling this story? What are you trying to say? What is your body trying to say?

I have one piece called The Creation by James Weldon Johnson, where I do the movement and speak, that Geoffrey Holder, my husband, had choreographed for me when I was at Yale. And that was a time when my body was really good and I enjoyed that feeling of movement. But as time had gone by, the legs start going. You know change. Life is life. And I found I couldn’t do that arabesque anymore. And I would worry about it sometimes, and then I thought to myself, Oh, for Pete’s sake, it’s a solo. Who’s gonna know? The less I moved, the more I heard the words. It was very interesting. So now I can sit in one place and tell this story and get the words out because now I don’t need the movement anymore.

It’s not about the counts. It’s about what you have to say. And I always say, “What is your story? Give me the word. Your foot doesn’t point, it points for a reason. It has a word. It’s saying something.” Like I said, [dancers] don’t have words to express that, so the body has to be the words. And we have to make it very clear to the audience what the story is so they can be a part of the story.

Can you recall any of the students you taught here?

Oh my goodness! I can’t remember everybody. My mind is a blur right now but they know who they are. It was wonderful watching them grow. I just loved it! When you see somebody that starts kind of rough and they work so hard. You see the growth and each year they get better and better and better. What really makes you feel good is when they leave, they get these wonderful positions and own companies. And some went off to teach children’s classes. Sometimes they’re choreographers. Sometimes they’re people who can be a good assistant to someone who needs it. So there are all kinds of ways of using dance. Now, a lot of people use dance to help young people emotionally. You know who you are!

Lester Horton said he predicted you’d do so many things with your life.

My mentor, Lester Horton, told me, “You know, there’s going to be a time when you’re going to have to not just dance. You’re going to have to sing. You’re going to have to act. You’re going to have to do it all.” And this was in the 1950s. He foresaw this and that’s what’s happening now. Young people, not only do you have to dance, now you have to act, now you have to sing because the theater has changed. The whole way of looking at dance, it’s not just one thing.

Nina Simone and Don Shirley were great concert pianists but they weren’t allowed to be concert pianist because of their color. They were told, “No, you can’t do that. You have to play jazz.” It was very hurtful for them because they wanted to be classical pianists. And now, you still don’t find classical pianists of color. But as far as dancing and films and television, my goodness! They’re stars. They can make a living out of it.

You know, Dorothy Dandridge almost made it. Beautiful lady, wonderful woman, lovely actor. Harry Belafonte, you know. But it didn’t go that far, did it? You look at the movies now and wow! They’re leading ladies and leading gentlemen. It’s amazing. But at that time we did not have that privilege, so you did what you had to do. You made do with what you had.

When you say we did not have that privilege, you mean because of discrimination?

Of course.

Can you tell me a little bit about Lena Horne? She was your sponsor.

My goodness, Lena Horne, the most beautiful woman in the world! In the movies they only gave her something to sing and when [the movies were shown in] the South, they pulled [the song] out. And even later, they never gave her a role. I think Dorothy Dandridge was the first time they gave a leading role to any woman of color. You see, at that time, it was just near impossible. She would’ve been so wonderful in film and it’s just sad.

Nobody sang like Lena. She was very kind to me. She sponsored me when I debuted at Lester’s in Salome. She was a charming, lovely woman. She would perform in Las Vegas. We went to visit her and met her husband and son. She had this big trunk full of books! And we said, “What are you doing with the books?” She was going to Las Vegas. She took the books to read because she couldn’t go to the swimming pool. She was the star of the show but she couldn’t use the pool! Pretty sad. When I performed in Las Vegas with Pearl Bailey as the star, the same thing, couldn’t use the pool. But you accepted those things and did the best you could. But times have changed.

My husband, Geoffrey, he didn’t care one way or another. He was born in Trinidad. And he was a genius. He was a painter, a director, an actor. He even cooked. I never met anyone liked him. I learned a lot from him because he was absolutely fearless. How can I say this? He said, “I walk through doors, and if the place doesn’t want me, there’s something wrong with the place, not me.” That’s the way he was. He didn’t care.

He introduced me to painters and interesting people. That was his aura. His life was being around people and everybody liked him and he was lots of fun besides. I learned a lot from him about design. He made all of my evening clothes. We would go to the Kennedy Center and I would get two dresses, one for the State Department and one for the White House. For 30 years, we did that. I have all of those dresses.

For further information, please contact:

Office of University Communications and Marketing

p – 516.877.3693

e – ucomm@adelphi.edu